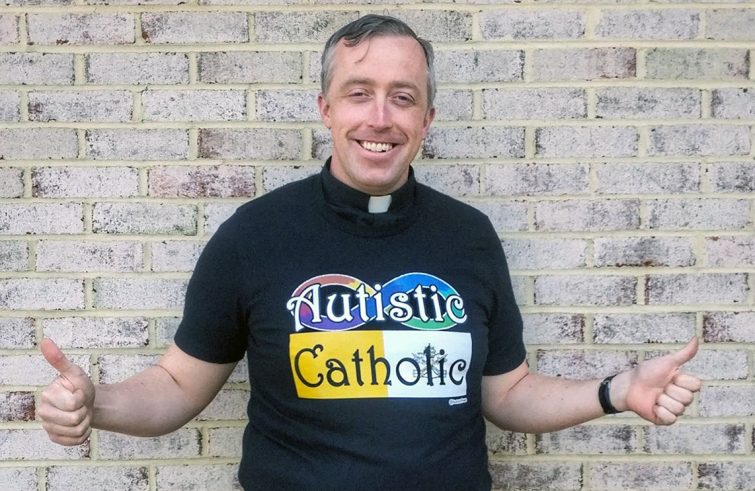

“Along with its areas of weakness, autism often creates areas of great strength, so look for those and see the overall beauty of autism whether you find them or not. Autism is a different mode of being, not all good or all bad.” Father Matthew Schneider is one of the most popular Catholic voices on social media (he has more than 65,000 Twitter followers). Most importantly, he is one of few priests to have been diagnosed with autism.

What does it mean to you to be an autistic priest?

To be a priest is to be one who is consecrated to the Father and who brings Jesus to people and people to Jesus. I was already ordained when I was diagnosed so I did not think about being an autistic priest beforehand. Now I think of it as something of a mission to share the Gospel specifically with my fellow autistics, since, having a similar neurology, I am often better able to communicate to them or “inculturate” the Gospel to our neurology.

Do we need to have a different pastoral sensitivity to the needs of autistic people?

I would start by promoting sensory-friendly Masses which are Masses with less loud sounds, lights, etc.

One effect of autism is that we tend to be more sensitive to lights and sounds, even ones that many people consider normal. Thus, some autistic people struggle to go to Mass because the lights and sounds can overwhelm them and cause a meltdown.

Also, having such a Mass helps with some of the judging autistic people feel people give us if we stim in mass (moving ourselves in ways like flapping hands to regulate ourselves), use sunglasses or ear plugs inside, or act in ways that some people find unusual.

- (Foto FB-FrMatthewLC)

- (Foto FB-FrMatthewLC)

What about confession?

Confession has several elements such as clarity about what is a sin, as we can sometimes consider a social issue we were unaware of or a passing thought as a sin.

For something to be a sin, we need to choose what we know to be wrong: if there is no choice or no knowledge of what is wrong (like unintentionally being rude), there is no sin.

Also, it is important to note that the Church teaches that everyone must communicate their sins to the priest for a valid confession. Most do this by talking but if an autistic finds it much easier to write on a piece of paper or use an iPad, this is perfectly acceptable.

What advice would you give to your brother priests who need to interact with autistic people?

The biggest piece of advice I would give other priests is to ask an autistic person what they need. We generally prefer directness, and persons with autism spectre disorder vary a lot in what they need: one may need a sensory-friendly Mass while another may find no help there but might need help navigating Church social events or other events of this kind.

Autism is not a monolithic condition where everyone has the same symptoms; it is more frequent to have at least some symptoms in a few categories.

Why did you choose “God Loves the Autistic Mind” as a title for your book? Was there any doubt?

I think for a book on prayer we have to focus on the relationship between the individual and God. The core element of that relationship is love. On the other hand, there are some things out there where people see autism purely negative and not something God would love. The book has one chapter on myths about autistic prayer and the two biggest ones might doubt “God loves the autistic mind.”

The first myth is that autism should be prayed out, and this can either stem from the belief it is related to demons or that it has a psychological origin and thus prayer is the cure to all, rather than having a perspective including both faith and science. Most of us do not want to be cured, simply helped live a full autistic life.

The second myth is often more implicit: it is the myth autistics cannot pray. Some make it explicit with how they understand the autistic abilities in theory of mind while others do so implicitly by having webpages about praying “for” your autistic child without one about praying “with” that same child.

Some saints were diagnosed with autistic spectrum, for example, Thomas Aquinas or Léonie Martin. Yet being diagnosed with autism is still something that frightens family members…

I don’t like to talk about post-mortem diagnosis, but I do see autistic traits in some like the two you mentioned, or in Tholák of Iceland, and Christina the Astonishing. We can look to them as examples. In my book, I mention all four of these in stories in the second half which is 52 short daily devotions. Autism can still be scary for parents for several reasons. Despite more information being in the public, it is still a bit of an unknown and there is a natural fear humans have for the unknown.

Also, it can be more difficult to get through school, get a good job, and find a marriage partner if autistic. These are real challenges that autism does make more difficult. However, at the same time, this is your same child you’ve always had and the diagnosis and awareness you now have likely increases your chances in these matters.

Along with the areas of weakness, autism often creates areas of great strength, so look for those and see the overall beauty of autism whether you find them or not. Autism is a different mode of being, not all good or all bad.

When did you realize that you were autistic?

I was diagnosed in January 2016. The weekend before I had gone to the Catholic Social Ministries Gathering and asked people how Catholics could better live Catholic social teaching, but I did not edit it together into a video until after I received a diagnosis. When I asked Bob Quinlan from the National Catholic Partnership on Disability about this, he spoke of how we need help the disabled not just be ministered to but become ministers as well:

“I’m not just trying to help them out on a one-way channel that comes back and helps me. I want to help them become good, to help them to give back as they can.”

This struck me when editing right after my diagnosis as it told me not to just go sit in a corner and be sad about my diagnosis but to use it in some way to help others.

Paradoxically, did the diagnosis help you in your ministry?

In a different way, my first year of priesthood was important. As a religious brother, I had done pretty well working in youth ministry, so I got assigned as a K-12 school chaplain for three years. After my first year, I realized I’d made a few mistakes but I thought it was a normal learning curve. Then the principal told me after a year that he did not want me back and suggested that I look into autism or Asperger’s, as I was not reading the children’s social signs well at all. That was a big turning point as had I never been told that or gotten some other ministry, I might still be struggling in ministries not particularly suited for me, while the diagnosis helped me to focus on ministries more in tune with my strengths.