“Welcome to a city without water, a city without electricity, a city without food, a city without medicine. Welcome to Sarajevo in the 1990s.” These are the opening lines of “War Childhood”, Jasminko Halilovic‘s book of memories of the 1,425-day siege of Sarajevo that left a brutal and indelible mark on the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav war. To rewind the tape of horror, Halilovic collected the memories of children, those who suffered most (and endured the consequences) of the conflict. “I have learnt that growing up during the war is a difficult, poorly researched and universally experienced predicament,” explains the author, who drew inspiration from these pages to give further prominence to the notion expressed in the book. The War Childhood Museum, devoted – literally – to wartime childhood, was in fact established in 2015. Visitors to Sarajevo cannot fail to make a stop at this museum, which takes those who cross its somewhat hidden threshold down the narrow streets leading to Bascarsija (the Old Town) back thirty years, to the tragedy that bloodstained the Balkans for years.

In total silence. Three small exhibition rooms, an itinerary into the experiences of children who lived through the war in Bosnia through the objects they once owned, surrounded by utter silence, characterize this unique museum, awarded in 2018 by the Council of Europe for its outstanding mission. “The vision of the War Childhood Museum is to help individuals overcome past traumatic experiences and prevent the traumatisation of others, while at the same time promoting mutual understanding on a collective level in order to foster personal and social development,” reads the exhibit description.

On entering the exhibition, visitors are immersed in an engaging sensory experience:

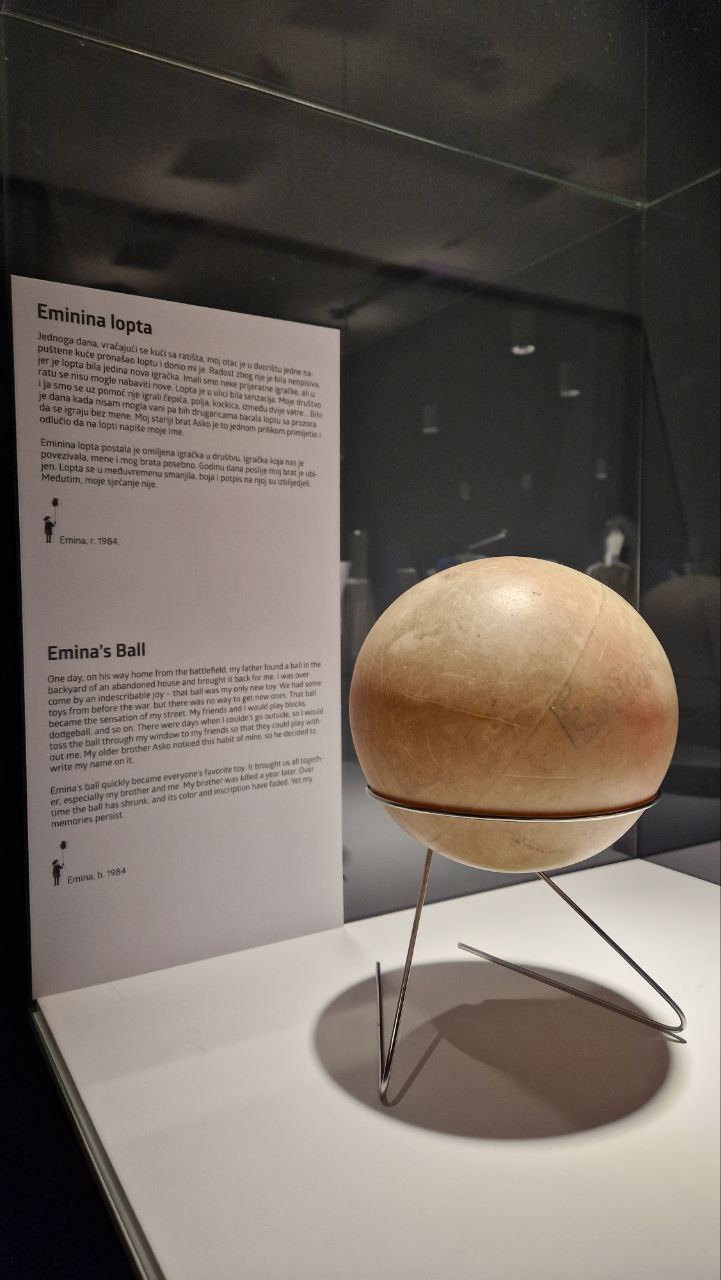

Different sounds are heard, from the rustle of grass to the bounce of a ball in a sports hall, selected scents or stickers under selected citations evoke childhood memories. The next room is a drastic departure. A multicoloured swing with a jingling bell to tell parents “I’m here!”, a blue stuffed rabbit, a rubber ball with the inscription “Emina” – after the owner’s name. The museum’s collection includes more than six hundred objects collected over the years, which belonged to children who experienced the tragedy of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a description of each item provided by the owners and the motivation for donating what is often the only memento of a missing family member.

- (Foto S.M.)

- (Foto S.M.)

- (Foto S.M.)

Indelible memories. “My father was a teacher, always clean-shaven and neatly dressed. As a child, I often watched him shaving and getting ready for work. He didn’t survive the Srebrenica genocide. I looked after this razor with care for many more years. Whenever I tried to use the razor, it would bring back memories of my father and his boundless love for my mother, sister, and me. I know I would never be able to use it as skillfully as he did, so I am giving it to the Museum for safekeeping.” This story told by Emir, who was only fifteen during the war, is but

one of the many testimonies that leave visitors shuddering at the thought of what that person’s childhood was like in comparison to their own,

remembered just a few moments earlier in the adjacent room. This dichotomy is a painful slap in the face, the blow that hatred inflicts on humanity during childhood, which is the purest age of human development.

Other conflicts. Amidst colourful children’s clothes (‘The only new dress I got during the war”, from Vesna’s testimony) and untouched humanitarian items – be they UNHCR-labelled nylon scarves or tinned food – the Sarajevo Museum has gained two new collections of items from some of the world’s fiercest theatres of war in the past few months: Ukraine and the Gaza Strip. There is Hala’s bracelet, woven in the colours of the Palestinian flag. She lived in Malaysia for four years, where she learned that ” outside Gaza, life is different”. There is a stuffed animal in the shape of a small dog that “saved the life” of Dmytro, who, during an afternoon spent playing, ran out into the courtyard to retrieve his toy, narrowly missing the Russian missile aimed at his house. There is even a ruby-red purse on display that belonged to Vlada’s grandmother. She was killed in the bombing of her house in Popasna, just two days after bidding farewell to her grandchildren on their way to western Ukraine: “As time went by, I realised that Grandma is always with me, protecting me and helping me to build a better life, so I decided to donate this memento to the museum, so that her example may serve to support many others.”

“This swing will keep on swinging.” The last exhibition hall is a dark room with a swing similar to the one that opens the tour of wartime children’s objects. It’s completely white. A red thread hangs from the ceiling and a single spotlight reflects its shadow on the floor. “When you push on this swing, you give off kinetic energy, which is converted into potential energy when the swing reaches its highest point. Theoretically, in the absence of external action, the swing would never stop moving. You are leaving the War Childhood Museum, but this swing will continue to swing, just as life goes on after childhood during wartime. Because life lasts longer than us and our experiences.”

A symbolic city. At a time when the blood of thousands of innocent people has been shed relentlessly, to have a space where children’s memories stand as beacons of life in contrast to hundreds of bloodstained hands is a precious treasure that must be protected, in a city like Sarajevo, a city whose soul has the coexistence of diversity at its core. And its extraordinary uniqueness, yesterday as today.