Three years after the release of ChatGPT, generative artificial intelligence has become a regular feature in the daily lives of millions, influencing language, learning, and decision-making processes. Don Luca Peyron, Head of the Pastoral Ministry for Technological and Scientific Culture in the Archdiocese of Turin and one of the leading ecclesial experts on digital matters, offers a perspective that combines sociology, anthropology, and pastoral experience.

Three years have passed since the launch of ChatGPT. How would you describe the transformation that has occurred during this time?

ChatGPT, together with Covid, marked a turning point. The pandemic accelerated the shift to digital; generative artificial intelligence has made what was once perceived as complex more accessible. Its plug and play nature has removed barriers to entry, giving many the sense that everything is immediate and intuitive. This ease is the reason for its success, but also its fragility:

when a tool appears simple, one tends to overlook its limitations and delegate to the machine skills one does not possess.

(Foto Sovvenire)

What is the main risk involved?

For a long time, artificial intelligence was associated with specialist expertise. Now many use it thinking that technology can replace knowledge. The danger lies in believing one knows what one does not. It is like driving a car without a licence: the sense of control does not match actual ability and exposes people to new risks, especially among population groups lacking adequate critical tools.

Generative AI affects memory, language, and judgement. How do you interpret this?

We are witnessing a cognitive revolution. The machine not only provides answers but enters the processes by which we structure thought. That is why I say that the idol is no longer mute: it speaks, and does so without pause.

adolescence and youth, already marked by developmental fragilities, now find in AI a constantly available, resistance-free interlocutor.

This can create dependency, not only technical but emotional, because the machine does not judge and does not introduce conflict.

You also link this to the crisis of relationships.

The absence of adult role models drives many to turn to algorithms, which, however, do not assume educational responsibility. This fosters an illusion of competence and guidance that does not match reality. We already saw this in healthcare, where improvised diagnoses and misinterpretations were common with search engines, and now find more sophisticated—and dangerous—tools.

The speed with which technology enters critical sectors is also cause for concern.

The rapid introduction of these systems in justice, healthcare, and administration requires technical and cultural awareness. Often this awareness is lacking. Moreover,

the almost free access to tools that generate significant economic losses suggests that the stakes are geopolitical, not commercial.

Meanwhile, an increasing share of digital content is being produced by machines, with consequences for the quality of information and citizens’ critical faculties.

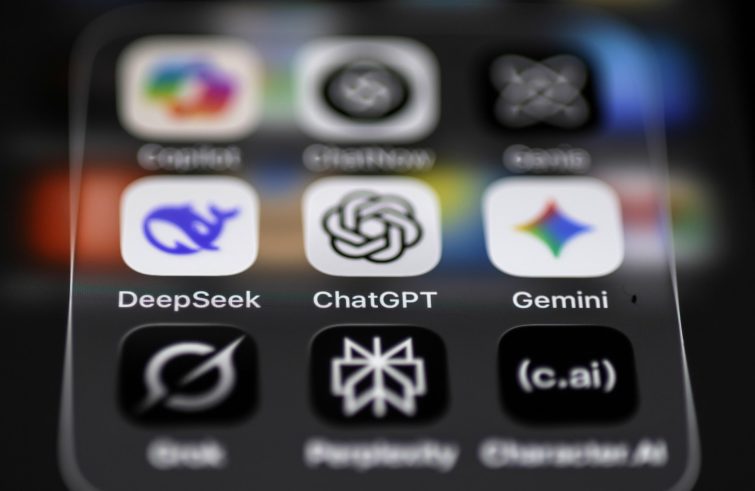

Launched on 30 November 2022, ChatGPT is the language model developed by OpenAI that brought generative artificial intelligence to the general public. Based on large neural network architectures trained on online texts, it produces textual responses, translations, analysis, code, and creative content in real time. Its spread has been among the fastest in the history of digital technologies, reaching the educational, professional, and administrative sectors.

From an educator’s perspective: is it time for more structured training?

Training is necessary, but without education it is not enough. A child must learn not only how to use an algorithm, but also how to leave it behind and return to manipulating the real world. Manual activity builds cognitive processes that digital tools cannot replace. If efficiency becomes the sole criterion, we risk reducing the human being to a function. Education must restore balance between doing and being.

Is this process reversible?

Yes, because every generation can rethink its relationship with technology. The notion of inevitability must be rejected: technology is not neutral; it incorporates values that must be directed.

just like medicine, algorithms that influence mental processes require criteria of responsibility. We cannot entrust the protection of vulnerability solely to economic logic.

The same applies to public administration?

A machine does not solve structural problems. Without appropriate reforms, AI risks becoming an excuse. There is also a question of sovereignty: public data cannot be managed lightly. And there is the energy issue, often ignored, concerning the impact of generative systems on global resources.

Pope Leo XIV frequently addresses the topic of AI. Can the Church accompany and guide this change?

The Church retains three decisive resources: the capacity to convene, a well-grounded anthropology, and a global presence. In a time marked by cultural fragmentation, it can offer places for listening, dialogue, and discernment. Every community can help people understand technology without fear and without naivety, preserving a vision of the human person not reduced to mere performance, but recognising the integral dignity of the person.