“Faith still has a relevance to life.” Don Luca Peyron, a priest from Turin and theologian specialising in digital culture, comments on one of the most profound passages in the address delivered by Pope Leo XIV to the Italian bishops: the section on anthropology and the challenges posed by artificial intelligence. It was, he says, “prophetic rather than circumstantial”, and reaffirms the mission of the Church in an age marked by technocracy. “The challenge,” he says, “is to think of our time in a Christian way, to safeguard and proclaim the dignity of the person as creature and mystery.”

The person is not a system of algorithms: it is creature, relationship, mystery.

(Foto ANSA/SIR)

In his address to the Italian Episcopal Conference, Pope Leo XIV said that “the person is not a system of algorithms: it is creature, relationship, mystery.” How do you interpret this passage?

It is not a formal invitation but a substantial choice. It is not a speech made for the occasion. The Pope wants this theme to enter the heart of reflection within the Churches, not only in Italy. From the very start of his ministry, he has placed artificial intelligence among the signs of the times. Pope Leo XIV does not speak only of technology but weaves together pastoral care and anthropology. When we teach catechism to children, we are addressing digital natives. When we speak of charity, we must also consider the existential gap generated by social media. And when we say “save”, our contemporaries think of a file. All this gives us pause for thought.

A priest of the Diocese of Turin, Don Luca Peyron is one of Italy’s leading experts in theology and digital culture. Founder and coordinator of the Digital Apostolate Service of the Archdiocese of Turin, he lectures at the Catholic University of Milan and the University of Turin. For years he has studied the impact of emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, on Christian anthropology and pastoral care. He has participated in various Synods and national conferences on the relationship between faith and innovation.

So an ethics of technology is not enough. Is something else needed?

Exactly. We cannot limit ourselves to providing criteria for governing technologies. We must offer a profound anthropology, one that serves as guide and prophecy. It is not enough to say “be careful, there are risks”. We are called to indicate a horizon of meaning and a goal for humanity immersed in the digital world.

“We cannot simply adapt what is known to what is new. We need a spiritual discernment that is born from Scripture.”

Does this address contain a synthesis of previous Popes?

It seems evident to me. Pope Leo XIV continues the path of Francis and, in certain respects, recovers insights of Benedict and Paul VI. What emerges is a Christologically founded anthropology: the true meeting point with the world. The humanity of Christ is a heritage that can be shared even by those who do not recognise his divinity. And Christ cannot be divided: by proclaiming his humanity, we proclaim the whole Gospel.

Why did Leo choose the Italian Episcopal Conference as the first to whom he addressed this appeal?

I believe it is a sort of “pastoral experimentation”. He is Bishop of Rome and chose his Episcopal Conference to relaunch a theme already entrusted by Francis to Catholic universities and dioceses. But it is now clear to everyone that it is time to act. We need to foster a cultural debate that has a soul: theological anthropology centred on Christ.

In his address to the Italian Episcopal Conference on 17 June 2025, Pope Leo XIV dedicated a central passage to the theme of artificial intelligence. “The dignity of the human,” he stated, “risks being flattened or forgotten, replaced by functions, automatisms, simulations. But the person is not a system of algorithms: it is creature, relationship, mystery.” The Pope asked the Italian Churches to adopt an anthropological vision as an essential tool of pastoral discernment, to prevent ethics from being reduced to code and faith from becoming disembodied.

What are the pastoral implications?

The implications are enormous. Every baptised person who bears witness to their faith is invited to rethink their testimony. We cannot simply adapt what is known to what is new. We need to revisit Scripture and Tradition so that the Spirit may suggest elements useful for discerning and guiding the present time.

Can you give a concrete example?

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus is called “maker of technology”. This is not a minor detail. It is a Christological title that we have scarcely explored over the centuries. If today a machine imitates the human, then that title acquires a new significance. The Gospels contain treasures that speak to every cultural season.

It is not a time for nostalgia, but for prophecy. The Church has a historic responsibility: to proclaim the human anew.

So it is not about updating what exists, but initiating a new exploration?

Precisely. We must not merely gloss what has already been said, but reapproach Scripture with new eyes. It is not a question of blame or shortcomings, but of a novum that asks to be discovered.

Does this require a change in mentality in pastoral practice?

We must abandon the logic of “finding those at fault” for what has not worked. It is not a time for nostalgia, but for prophecy. And today prophecy is lacking. There are no longer prophets of good fortune or doom. The Church has a renewed historic responsibility: to offer words and gestures that proclaim the fullness of the human to a humanity that is lost and searching for identity.

Can the Church still have an impact on people’s daily lives?

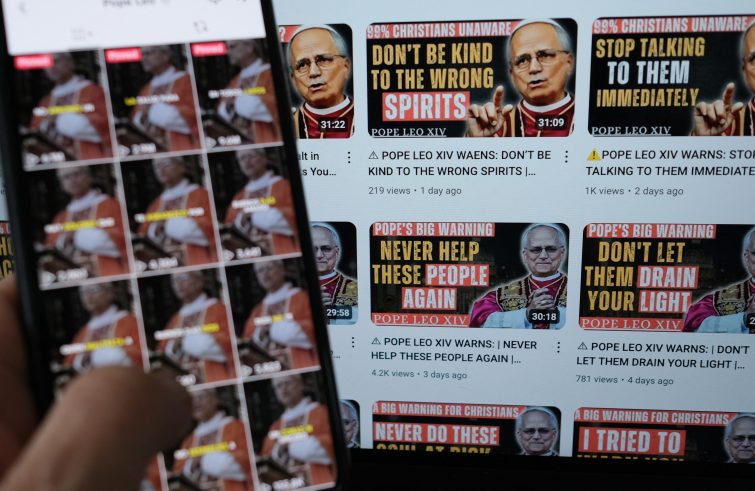

Every week we stand before hundreds of people. We do not have to give lessons on artificial intelligence, but proclaim Jesus Christ. But Christ is today, in this time. The preparation of those engaged in pastoral care must nourish the People of God with knowledge and prophecy. At stake are freedom, relationships, solitude. Faith. The pastoral care of culture is not for intellectuals: it is above all for simple people, who are too often at the mercy of “clickbait” headlines.

In the age of machines and digital virtuality, Christ remains the horizon in which the human can still be fulfilled.

What do you say to those who claim that the Church is always behind in science and technology?

That is a myth to be dispelled. The Church has two thousand years of history. Only for a few centuries and in certain circumstances have we retreated. For the rest, it has generated culture, science, and technology. From irrigation in the missions in Africa to the Big Bang of Le Maître, priest and cosmologist. The very idea of progress is a child of Christianity. Pre-Christian culture was cyclical. We introduced the word “fulfilment”. A journey, a pilgrimage, a growth. Today it is time to return it to the world.

Ultimately, what is the Church’s most urgent challenge?

Today we have a new opportunity to show that faith has a real relevance to life. Because life profoundly questions Christian faith: it demands incarnation and redemption, body and metaphysics. In the age of machines and digital virtuality, Christ remains the horizon in which the human can still be fully realised. Here and in eternity.