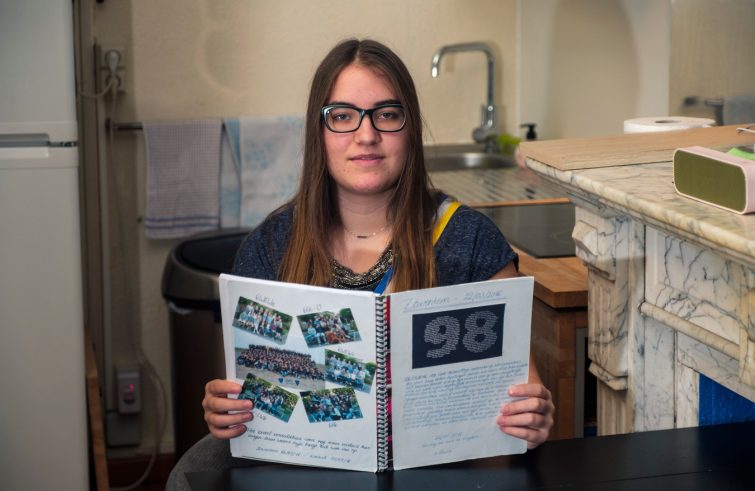

A young woman in Belgium, who died inside several years ago, was confronted with a disguised fake mercy law. After surviving the terrorist attack of 22 March 2016 at Brussels airport at the age of 17, but permanently psychologically and emotionally scarred, after six years of depression, panic attacks, hospital admissions and an attempted suicide, 23-year-old Shanti De Corte filed a request for euthanasia claiming “unbearable mental suffering.” “It is impossible and it would be unfair and presumptuous to claim to understand the mystery of the mind and soul of this young woman who took this decision, or that of her parents who accompanied her towards this tragic denouement with their hearts filled with grief. The one thing that prompts our reflection is her excruciating pain that makes us wonder about what sort of response she received”, Mario Pollo, anthropologist of education, former professor of Sociology and Pedagogy at Rome’s Lumsa University, told SIR. “We human beings are an animal symbolicum”, he explained. “We interpret every stimulus we receive from the surrounding environment on a symbolic level and our response depends on this interpretation. Those factors that give us the interpretive keys stem from the languages of our social culture that appear to have lost that ancient wisdom, connected to the Bible and to Greek culture, according to which joy and pain are intertwined and inseparable in human life.

On the contrary, today we believe that life can be entirely devoid of pain and we try to anaesthetise all forms of suffering through entertainment or by resorting to drugs, alcohol and/or medication.”

This numbing attempt prevents us from being in touch with our inner suffering and with our soul, thus preventing us from realising that even the experience of suffering can be an opportunity for growth and transformation. But there is more.

What?

We have lost the sense of life as mystery. The prehistoric man grasped its unfathomable nature. We, on the other hand, expect to provide an explanation of what life is about when in fact we can at best describe its biological mechanisms. Having somehow lost sight of this, we also lost the ability to love life authentically, in all its depth.

This love of life, even in the simplest things or in the most difficult situations, should be the subject of education for the younger generations.

Besides pharmacological treatment for the severe depression she was suffering from, what kind of answers might Shanti have needed?

I think that first of all she needed to be listened to. However, in order to be able to actually listen to another person’s pain, we must not have numbed the ability to listen to the suffering of our own soul, which should be acknowledged and embraced. Only by reaching out to that suffering are we able to understand another person’s pain in full, that very ”existential” suffering for which ”anaesthetising” strategies will not work. Listening, accompanying: the heart of the matter is

to help the other person, often entrenched in their pain, to try to make sense of their suffering – in this case also of the horrors this young woman had gone through.

It has been described as a severe form of depression; Jung describes it as the journey of someone who having lost contact with his vital energies, descends into his deepest inner self to rediscover the wellsprings of life and drink from them. This downward path is treacherous and it entails the risk of losing oneself and taking drastic steps. Depression must be treated pharmacologically, but we should not forget that it implies losing contact with the life beating within us, within our innermost being, which we must somehow recover. This path needs to be accompanied and supported.

We have no elements to say whether or not this young woman received this kind of support, but it is a question we cannot elude.

However, a law that allows people to end their own life, thus “clearing the way” for the euthanasia of a girl in her early twenties, a victim of “unbearable psychic suffering”, is disturbing.

That is why, as I said, the main problem of our culture is the ability to accept that suffering is part of our and other people’s life and, because of that, we must console those who suffer by helping them give meaning to their experience.

Doesn’t the message that there is no other way out but death send a dangerous signal of despair to today’s increasingly fragile and lonely young people?

It does. I have been working on a reflection concerning the signs of death present in our culture, on the thought that life has no meaning except in seemingly fulfilling things, or if it meets the criteria of health, autonomy and efficiency set by society. I would like to give renewed emphasis to a cultural proposal for the education of young people that puts the beauty of life back at the centre, encouraging the young to love life even when everything seems negative. Today we are confronted with a sort of robotisation of the human being that excludes inner life, an aspect that a society that cares for its young people should concentrate on.

With profound respect for Shanti and for her poor parents, who will suffer an open wound for the rest of their lives. This episode should serve as a wake-up call to rethink our cultural paradigms and educational models, ensuring that no one will ever consider death as the only possible option.